Research

Synchronization of coupled oscillators

How can thousands of fireflies flash on and off in unison, all night long, without any leader or cue from the environment? More generally, how can dissimilar oscillators all come to act as one, in diverse biological, physical, and chemical systems? Over three decades of work on modeling such systems, using nonlinear dynamics, statistical physics, and computer simulations, has deepened our understanding of synchrony in our bodies and the world around us.

-

Synchronization of Pulse-Coupled Biological Oscillators (PDF)

– SIAM Journal on Applied MathematicsCoupled Oscillators and Biological Synchronization (PDF)

– Scientific American -

All Together Now (PDF)

– NatureAll Together Now (PDF)

– NatureStep in Time (PDF)

– Science NewsFlirting Male Crabs Found to Wave Claws in Unison

– The New York TimesA Mystery of Nature: Mangroves Full of Fireflies Blinking in Unison

– The New York Times

Small-world networks

How can all eight billion of us be just six handshakes apart? “Small-world networks,” introduced by Strogatz and his former graduate student Duncan Watts, give one possible explanation. The same math also gives insight into how epidemics spread, how brains are wired, and how blackouts propagate through the power grid.

-

-

It's a Small World (PDF)

– Nature News and ViewsMathematicians Prove That It's a Small World (PDF)

– The New York TimesSmall World (PDF)

– Cornell Magazine

A Networked World (PDF)

– Physics World

Charged knots

If you spread electric charge uniformly along the length of a knotted curve, what do the equipotential surfaces around the knot look like? How does their shape change as you move close to the knot or far away? And how many equilibrium points are there in the surrounding electric field? Questions like these are natural starting points for the new subject of electrostatic knot theory.

Global synchronization

Imagine many rhythmically pulsing heart cells or flashing fireflies. If you want them all to end up in sync — no matter how disorganized they are at the start — how should you connect them? In other words, what kinds of network structures favor global synchrony?

How a minority can win

Even in the absence of rigging, voter suppression, or other malfeasance, strange things can occur in elections. For example, suppose people turn out to vote only if they think the election is going to be tight. If they base that assessment solely on what they’re hearing from their friends and neighbors, then in a simple model we can quantify how often unrepresentative outcomes occur, in which a less popular candidate wins by generating higher turnout.

-

-

Modeling Suggests Friendships May Lead to Lopsided Elections

– Cornell Chronicle

Metronomes that fall into step

When two or more metronomes are placed on a platform that can move from side to side, they tend to synchronize their swings, as if they were trying to cooperate. The phenomenon seems unbelievable at first, and videos of it on YouTube have garnered millions of incredulous views. Equally surprising, the phenomenon is still not understood mathematically. These papers shed new new light on the puzzle.

Mutations spreading through a network

In fields ranging from cancer biology to evolutionary game theory, it’s important to understand how a tiny group of mutants can spread and ultimately take over a much larger population of normal individuals. How does the time for mutant takeover depend on the network structure of the population? Mathematical models provide an answer, and may explain why the incubation periods for many diseases show strongly right-skewed distributions, with some people taking much longer than others to show symptoms.

-

Evolutionary Dynamics of Incubation Periods (PDF)

– eLifeTakeover Times for a Simple Model of Network Infection (PDF)

– Physical Review EFitness Dependence of the Fixation-Time Distribution for Evolutionary Dynamics on Graphs (PDF)

– Physical Review EAsymptotic Absorption-Time Distributions in Extinction-Prone Markov Processes (PDF)

– Physical Review Letters -

Why Don’t Patients Get Sick in Sync? Modelers Find Statistical Clues

– Quanta Magazine

Swarmalators

Most research on self-organization has focused on groups that coordinate themselves in time (synchronously flashing fireflies, chorusing crickets) or in space (flocks of birds, schools of fish). What happens in systems that do both? A mathematical model of swarming oscillators, or “swarmalators”, suggests new directions in engineering and biology, from the design of fleets of robotic drones to the group behavior of Japanese tree frogs.

-

Oscillators that Sync and Swarm (PDF)

– Nature Communications -

Swårmalätørs

– Complexity ExplorablesSelf-organization in Space and Time

– SIAM NewsStrogatz’s Study of ‘Swarmalators’ Could Direct Future Science

– Cornell Chronicle

How one new thing leads to another

The old adage that one thing leads to another may have surprising scientific implications for anything that evolves. By opening new possibilities, a novelty or innovation can pave the way for others in a process that Stuart Kauffman has called ‘‘expanding the adjacent possible.” Strogatz and his colleagues have taken a first step toward modeling the adjacent possible mathematically and exploring its role in biological, cultural, and technological evolution.

-

The Dynamics of Correlated Novelties (PDF)

– Scientific ReportsDynamics on Expanding Spaces: Modeling the Emergence of Novelties (PDF)

– Creativity and Universality in Language -

Mathematical Model Reveals the Patterns of How Innovations Arise

– Technology ReviewThe Mathematics of Discovering New Things

– The Washington PostThe Mathematics of Novelties and Innovations

– Wired.com

Urban mobility

What’s the minimum number of taxis it would take to meet the demand in New York City, if the cabs were dispatched optimally? If people shared taxis with strangers, how much money could be saved? And how much could pollution and traffic be reduced? A dataset of 150 million taxi trips and a new type of mathematical analysis enabled the untapped potential of New York City’s fleet of more than 13,000 taxis to be quantified.

-

Quantifying the Benefits of Vehicle Pooling With Shareability Networks (PDF)

– Proceedings of the National Academy of SciencesScaling Law of Urban Ride Sharing (PDF)

– Scientific ReportsAddressing the Minimum Fleet Problem in On-Demand Urban Mobility

– Nature -

If Two New Yorkers Shared a Cab...

– The New York TimesOptimizing Taxi Fleet Size the Subject of Multi-University Research

– Cornell Chronicle

Dynamics of social balance

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend” – what are the mathematical consequences of playing out this logic in large social or political networks? Tools from statistical physics, graph theory, and random matrix theory bring out the surprising implications of this ancient approach to friendship and rivalry.

-

Energy Landscape of Social Balance (PDF)

– Physical Review LettersContinuous-Time Model of Structural Balance (PDF)

– Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences -

Dynamics of political moderation

In a simple model of a society polarized by ideological conflict, how can moderation be encouraged? Under what conditions will a committed minority of true believers eventually win everyone over to their point of view?

-

Encouraging Moderation: Clues From a Simple Model of Ideological Conflict (PDF)

– Physical Review Letters -

Chimera states for coupled oscillators

Systems of identical oscillators with symmetrical coupling can sometimes split into two domains, one synchronized, the other desynchronized. The properties of such a “chimera state” have been elucidated by exactly solvable models.

-

Chimera States for Coupled Oscillators (PDF)

– Physical Review LettersSolvable Model for Chimera States of Coupled Oscillators (PDF)

– Physical Review LettersSolvable Model of Spiral Wave Chimeras (PDF)

– Physical Review Letters -

Exotic Chimera Dynamics Glimpsed in Experiments (PDF)

– Physics TodayNews and Views: Spontaneous Synchrony Breaking (PDF)

– Nature Physics

Crowd synchronization on the Millennium Bridge

What caused London’s Millennium Bridge to wobble on its opening day? And why did the pedestrians on it inadvertently fall into step with its sideways vibrations? A model based on ideas from mathematical biology explains both effects as two sides of the same coin.

-

-

All Together Now: Synchrony Explains Swaying

– The New York TimesFew People 'Caused' Bridge Wobble

– BBC NewsExplaining Why the Millennium Bridge Wobbled

– Science DailyRevealed: Why London's Millennium Bridge Wobbled

– ReutersMillennium Bridge Wobbles Are Explained at Last

– The TelegraphMillennium Bridge Wobble Explained

– Financial Times

Dynamics of language death

The world’s languages are vanishing at an alarming rate. Modeling the competition between languages with the tools of population dynamics led to the first quantitative model of language decline.

-

-

'Status' Drives Extinction of Languages

– ABC ScienceGaelic 'Extinct in 40 Years'

– Scottish Daily RecordLanguage's Status Drives its Survival

– Discovery News

Percolation on random graphs

Mathematical studies of the Internet, social networks, and the power grid have addressed the resilience of these networks to either random or targeted deletion of network nodes. Percolation models on random graphs with arbitrary degree distributions can be solved exactly to illuminate this issue of network resilience.

-

Network Robustness and Fragility: Percolation on Random Graphs (PDF)

– Physical Review LettersRandom Graphs with Arbitrary Degree Distribution and Their Applications (PDF)

– Physical Review E -

Dynamics of Josephson junction arrays

Josephson junctions are superconducting electronic devices that obey the same governing equations as pendulums – but they swing a hundred billion times faster. When thousands of them interact, how do they behave?

-

Synchronization Transitions in a Disordered Josephson Series Array (PDF)

– Physical Review Letters -

Keeping the Beat (PDF)

– Science News

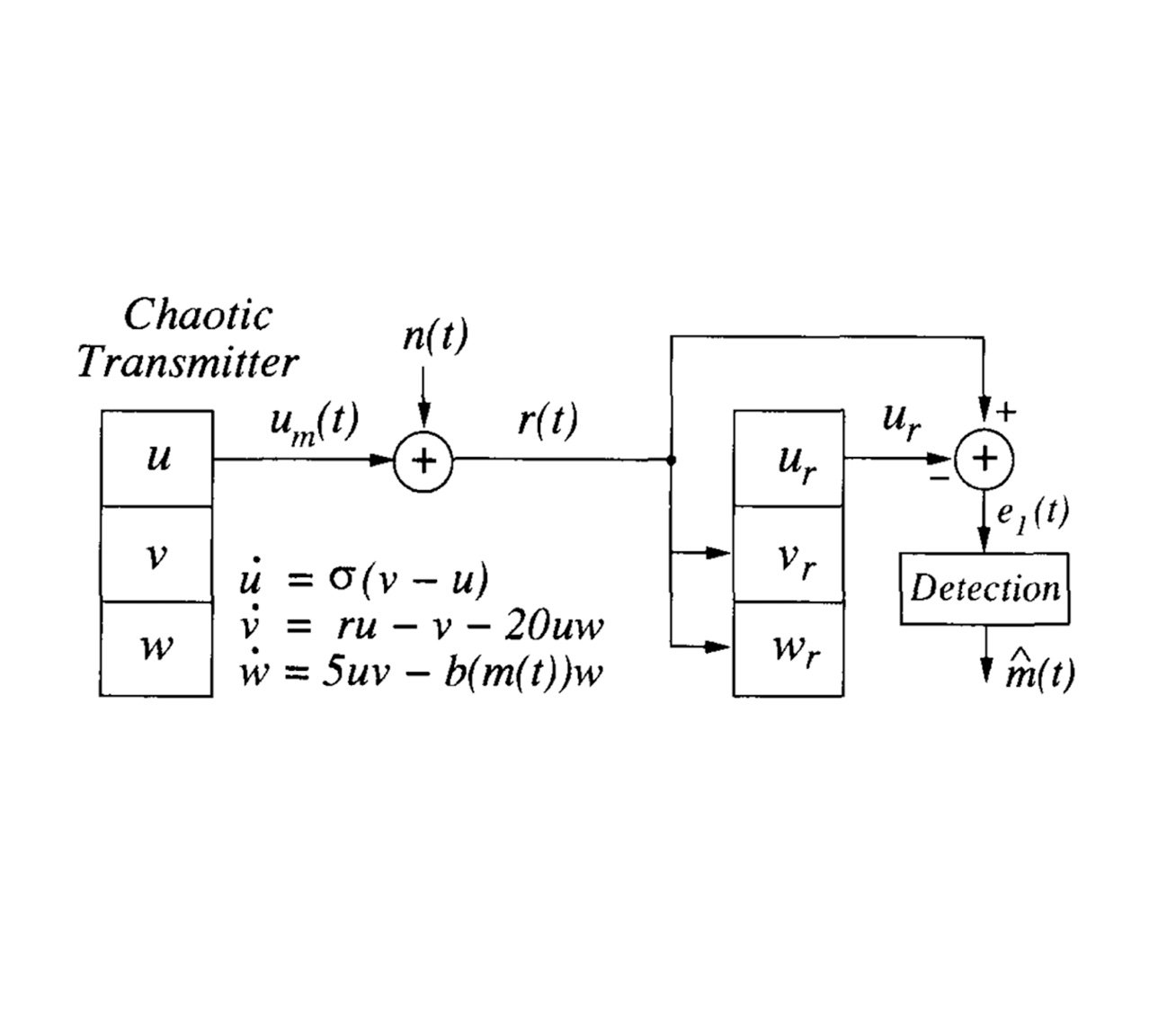

Sending secret messages with synchronized chaos

A pair of synchronized chaotic circuits can be used to create a new kind of communication system. Moreover, a message becomes more private when it’s cloaked in chaos.

-

Synchronization of Lorenz-Based Chaotic Circuits, With Applications to Communications (PDF)

– IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems -

Dynamics of switching in charge-density waves

A charge-density wave is like a block of jello on a sticky plate. If you tug it sideways, it stays stuck in place … unless you tug it just hard enough; then it breaks loose and starts to slide. A coupled oscillator model showed that the sliding speed could depend discontinuously on the tugging force – as previously seen experimentally.

-

Simple Model of Collective Transport With Phase Slippage (PDF)

– Physical Review LettersCollective Dynamics of Coupled Oscillators With Random Pinning (PDF)

– Physica DDelayed Switching in a Phase-Slip Model of Charge-Density Wave Transport (PDF)

– Physical Review B

Data analysis of human sleep and circadian rhythms

Studies of brave volunteers living for months in underground caves or windowless apartments have clarified how bright light shifts our circadian rhythms, why many of us like to take an afternoon nap, and why it's so hard to fall asleep two hours before your regular bedtime.

Topology of scroll waves

Spiral waves of activity occur in thin layers of heart muscle, nerve tissue, and certain chemical reactions. Scroll waves, their three-dimensional cousins, can be twisted, linked, and knotted according to a topological exclusion principle.

-

Organizing Centres for Three-Dimensional Chemical Waves (PDF)

– NatureYeast Oscillations, Belousov-Zhabotinsky Waves, and the Non-Retraction Theorem (PDF)

– Mathematical Intelligencer -

Strange, Scroll-Like Wave Is Linked to Biological Processes

– The New York Times

Topology of chromatin and supercoiled DNA

The linking number of DNA helps us unravel the structure of the chromatin fiber, the next level of coiling above the double helix and below the chromosome.

-

Structure of Chromatin and the Linking Number of DNA (PDF)

– Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Einstein's boyhood proof of the Pythagorean theorem foreshadows the scientist he later became.

- The New Yorker

November 19, 2015